RMO 2024 Sketches

I solved the RMO problems today after the exam. I am documenting the solutions and my feelings of difficulty (out of 5) for each problem. I hope you enjoy the solutions. Let me know if you liked it, and share the solutions with interested people.

RMO difficulty feeling: 1.

Straightforward problem. The invariant of part a is standard. The second part is not too convoluted and is something most people will try. It’s a good beginner problem that sets the mood and eases the participant.

Proof:

(a) Suppose n is odd and $a_1,a_2,\ldots a_n$ is a nice rearrangement. Since $a_1,a_2,\ldots a_n$ is a permutation of $1,2,3,\ldots,n$ it is immediate that \[a_1 + a_2 + a_3 +\ldots + a_n = 1+2+3+\ldots+n=\frac{n(n+1)}2.\] Since $n$ is odd, we note that $n(n+1)/2$ is a multiple of $n$ since $n+1$ is even. This contradicts the niceness of the rearrangement since $a_1 + a_2 + a_3 +\ldots + a_n$ is a multiple of $n$.

(b) If n is even, we claim the rearrangement $2,1,4,3,6,5,8,7,….n,n-1$ is always nice.

The proof is by induction on $n$. For $n=2$, clearly $2,1$ is nice since 2 does not divide 3. Suppose we have proved the claim for some even n, then we show the claim holds for n+2. For n+2, we already know $a_1 + a_2 + a_3 +\ldots + a_k$ is not a multiple of k for $k \leq n$ by induction. Next we note that $a_1+\ldots+a_{n+1} = n(n+1)/2 + (n+1)+1$ which leaves a remainder of 1 when divided by $n+1$ since the first two terms are multiples of $n+1$. And finally \[a_1 + a_2 + a_3 +\ldots + a_{n+2} = \frac{(n+2)(n+3)}{2}.\] The number $\frac{(n+2)(n+3)}{2}$ is not divisible by $n+2$ since the quotient $\frac{(n+3)}{2}$ is a fraction (because n+3 is odd). Thus $a_1 + a_2 + a_3 +\ldots + a_{n+2}$ is not a multiple of $n+2$. Thus the claim is proved for $n+2$. So the proof of the statement “the rearrangement $2,1,4,3,6,5,8,7,….n,n-1$ is always nice” is complete.

RMO difficulty feeling: 2.

RMO difficulty feeling: 2.

Straightforward to guess the answer by trial and error. But proving it requires you to note that $R(n) > n$ eventually. Now $R(n)$ grows as $n^2$ so there will be many ways to do this proof. The proof writing is the main focus of this question since the idea is pretty simple. It’s rated 2 because of the algebra can get messy for a beginner.

Proof: The key idea is to note that by division algorithm if $a,b$ are natural numbers, then \[a = \left\lfloor \frac{a}{b} \right\rfloor b+ r\] where r is the remainder when a is divided by b. So we have a formula for $R(n)$: \[ R(n) = \sum_{k=1}^n \left(n - \left\lfloor\frac{n}{k}\right\rfloor k\right)\] We note that for $n \geq k > n/2$, we have $1 \leq \frac{n}{k} < 2$. Thus $\lfloor n/k\rfloor = 1$ for this range. The terms in this range are summable and we thus obtain a bound for all $n$: \[R(n) \geq \sum_{k > \lceil n/2\rceil}^n (n-k) = 1+ 2 +\ldots + \left(\lceil n/2 \rceil -1\right) \geq \dfrac{n/2(n/2-1)}{2} = \dfrac{n(n-2)}{8}.\] In the problem, we want to solve for $R(n) = n-1$. Suppose $m$ solves the equation, then \[m-1 = R(m) \geq \dfrac{m(m-2)}{8}.\] Thus we solve the quadratic inequality to get \[8m-8 \geq m^2-2m \implies m^2 -10m + 8 \leq 0 \implies m \leq 9.\] Thus we have to check the first 9 numbers only. We see \[R(1)=0, R(2)=0, R(3)=1, R(4)=1, R(5)=4,R(6)=3,R(7)=8, R(8)=8, R(9)=12,\] thus $1,5$ are the only solutions.

RMO difficulty feeling: 3.

I wonder if there is a synthetic solution. All the lengths in the problem make it clear that most solutions will mostly be length bash based. Since there is a busy right angled point (D), it is suitable for a coordinate bash. Sophisticated coordinates computation is not a part of school syllabus and further one should either know various facts or compute heavily to get the relation between coordinates and figure out $a^2=24$.

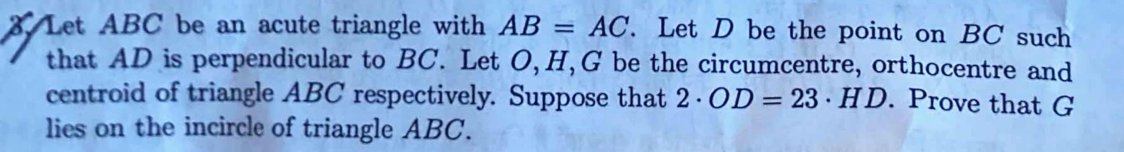

Proof: The proof is a straightforward coordinate computation. We have labelled the circumcentre as S instead of O. Look at the diagram below where S, G, I, H are the circumcentre, centroid, incentre and orthocentre of triangle $ABC$, respectively.

Note that $G=\left(0,\dfrac{a}3\right).$ It is well known that G trisects the segment SH (often proved as a part of the Euler line theorem), we have \[2(0,s)+(0,h) = 3(0,a/3)\] and thus $2s+h=a$. It is given in the problem that $2|DS| = 23|HD|$ and thus $2s=23h$. So we have \[h = \frac{a}{24}, \,\, 2s = \frac{23a}{24}.\] Since $S$ is the circumcentre, we must have $|SA|=|SB|$ and thus \[(s-a)^2 = s^2+1.\] Rearranging we get \[a^2-2as = 1 \implies a^2 - (23a^2/24) = 1 \implies a^2 = 24.\] Now this means we compute sidelengths \[|AB|=|AC| = \sqrt{a^2+1}= 5, \,\, |BC|=2.\] Using the angle bisector lemma, we can say that I divides $AD$ in the ratio $|AB|:|BD|=5:1$ and thus \[\dfrac{|AI|}{|ID|} = 5 \implies I = \dfrac{5(0,0)+1(0,a)}{6}=\left(0,\dfrac{a}6\right).\]Since $ID \perp BC$, $D$ is a touch point of the incircle with line $BC$.So $D$ lies on the incircle and the line $ID$ is a diameter. Since $G$ lies on the line $ID$, in order to show $G$ is on the incircle, it suffices to show $GD$ is a diameter. So we show that $I$ is the midpoint of $GD$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of $GD$, \[M = (G+D)/2 = (\left(0,\frac{a}3\right)+(0,0))/2 = \left(0,\frac{a}6\right) = I.\] So $G$ lies on the incircle of $\triangle ABC$.

RMO difficulty feeling: 5.

I think this is the hardest problem in the set. In the solution, I will leave algebraic manipulation to the reader since it is boring to watch other people do algebra. While I finished the rest of the paper in 75 minutes, this problem alone took over an hour! I generally try brute forcing algebra only when I am at my wits’ end. Brute forcing the algebra worked here and it was not all that hard. The hardness is due to the fact that none of the standard inequalities like AM-GM, Cauchy-Schwarz worked when I tried. Adding the inequalities was weak. Adding them in batches failed too. It needed raw thinking and no theorems helped me. So its a 5 in my heart.

Proof: We will prove the inequality by contradiction. In fact we will contradict the constraint \[a_1^2+a_2^2+a_3^2+a_4^2=1.\]Without loss of generality, assume $a_4 \leq a_3 \leq a_2 \leq a_1$. Suppose for all $1\leq i < j \leq 4$, \[(a_i-a_j)^2 > \frac15.\] Thus we have \[ a_1-a_2 > \frac1{\sqrt{5}},a_2-a_3 > \frac1{\sqrt{5}}, a_3-a_4 > \frac1{\sqrt{5}}. \] Now set \[a_1-a_2-\frac1{\sqrt{5}}=x,\] \[ a_2-a_3-\frac1{\sqrt{5}}=y,\] \[a_3-a_4 -\frac1{\sqrt{5}} =z,\] and note that $x,y,z > 0$. Rearranging and back-substituting the variables we get \[a_3 = a_4 + \frac1{\sqrt{5}} + z,\] \[a_2 = a_4 + \frac2{\sqrt{5}} + y+z,\] \[a_1 = a_4 + \frac3{\sqrt{5}} + x+y+z.\]

Now it can be shown that (meaning you should do some work!) \[a_1^2 +a_2^2+a_3^2 + a_4^2 = \left(2a_4+\dfrac{3x+2y+z+\dfrac{6}{\sqrt{5}}}{2}\right)^2 + 1 + \dfrac{3x^2}4+y^2+\frac{3z^2}4 + xy+yz+\dfrac{xz}2+\dfrac{3x+4y+3z}{\sqrt{5}}.\]The expression on the right-hand side is greater one, since $x,y,z > 0$, which contradicts the given constraint.

RMO difficulty feeling: 1.5.

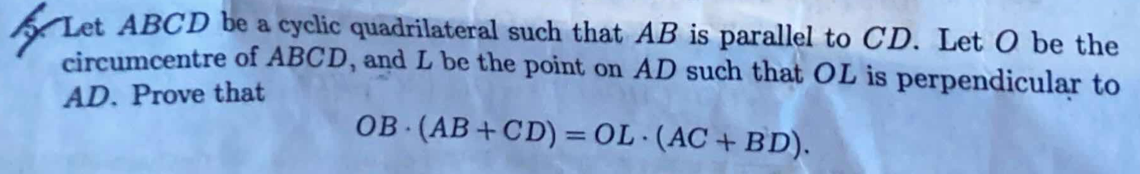

It’s a pleasant and straightforward problem, once you realise that you can do it by trigonometry. A single cyclic quadrilateral with angle conditions is usually a poster boy for trigonometry problems.

The problem is pretty cute, though, and I will include it as an application of the sine rule in my geometry courses. The proof is straightforward once you have chased angles. I like cute and sweet problems in the Olympiad.

Proof: We proceed by trigonometry and sine rule. Let $R$ be the radius of the circle. Consider the following figure, which has angles marked.  We have used the parallel lines to mark alternate angles equal and we have also used angles in the same segment are equal. We have to show \[OB(AB+CD) = OL(AC+BD).\] First we note that $OL = R \cos \alpha$ by applying the definition of $\cos \alpha$ in $\triangle AOL$. Using extended sine rule, we have to show \[R(2R\sin (2\alpha+\beta) + 2R\sin \beta) = R\cos \alpha (2R \sin (\alpha + \beta)+ 2R \sin (\alpha+\beta)).\] which reduces to proving

We have used the parallel lines to mark alternate angles equal and we have also used angles in the same segment are equal. We have to show \[OB(AB+CD) = OL(AC+BD).\] First we note that $OL = R \cos \alpha$ by applying the definition of $\cos \alpha$ in $\triangle AOL$. Using extended sine rule, we have to show \[R(2R\sin (2\alpha+\beta) + 2R\sin \beta) = R\cos \alpha (2R \sin (\alpha + \beta)+ 2R \sin (\alpha+\beta)).\] which reduces to proving

\[\sin (2\alpha + \beta) + \sin \beta = 2 \cos \alpha \sin (\alpha+\beta).\] But this simply follows from applying $\sin x + \sin y = 2\sin \left(\dfrac{x+y}{2}\right)\cos \left(\dfrac{x-y}{2}\right).$

Comment: My student Rishon Fernandes pointed to me that this problem is a subproblem of British Math Olympiad 2022 Round 1, Problem 5.

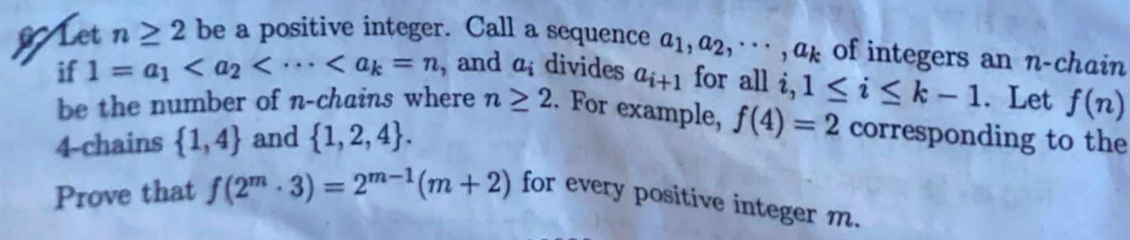

RMO difficulty feeling: 3.

Nice problem. This problem is asking for the number of chains in a divisor lattice. In fact if $f(n)$ denotes the number of chains of divisors of $n$, then one can easily prove the recursion \[2f(n) = \sum_{d \mid n} f(d).\] I thought Mobius inversion and the associated techniques will be useful. I like the question since it is steeped in Lattice theory and it is asking for a special case. So it has room for exploration and tingles the scientist in me.

As a RMO problem, either you had to set-up a recursion, or solve it by bijecting it to some associated problem like I did in my solution below. There are many lines of attack and all of them involve some careful computation. Since it has many approaches, my difficulty feeling is lower. The difficulty rating is still 3 since writing a clear solution is tricky and the use of the bijection/recursion to get to the answer is non-trivial.

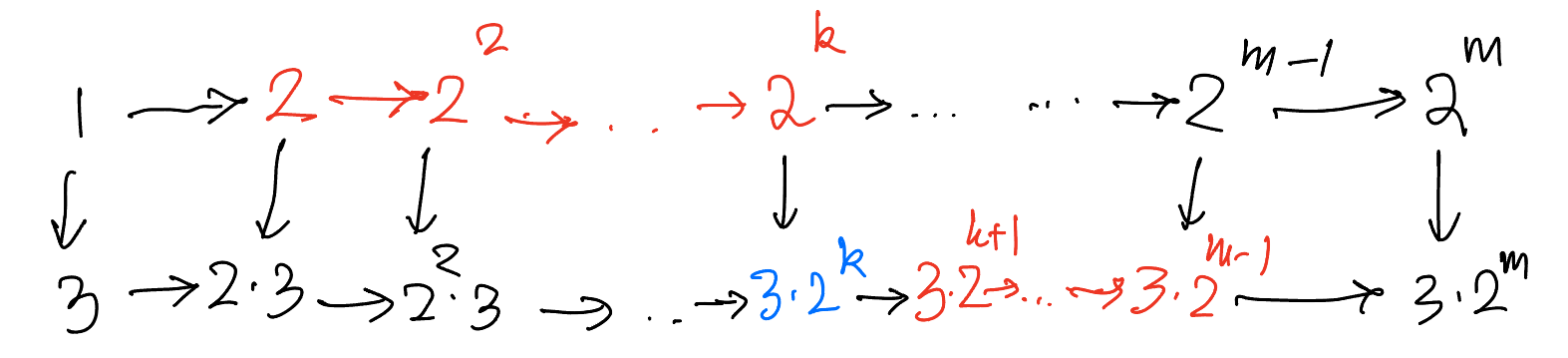

Proof: We write the divisors of $3\cdot 2^m$ in the form of a diagram shown below (ignore the colors for now). In the diagram, if there is a path from a to b, then a divides b .

A maximal chain is a chain that cannot be enlarged by including an divisors. Every chain is contained in a maximal chain and every maximal chain has length $m+2$. In the directed graph shown, a maximal chain is a directed path starting from 1 and ending at $3\cdot2^m$. Since 1 is on the top and $3.2^m$ is on the bottom, a directed path must switch from top to bottom exactly once (since in this graph, we cant go up once we are on the bottom row). Suppose the switch happens at $3\cdot 2^k$ as shown in the figure, for $k=0,1,2,\cdots,m$.

For $k \neq m$, any chain that is a part of this maximal chain contains 1, $3\cdot 2^k$, $3\cdot 2^m$ and we are free to choose a subset of the remaining $m-1$ elements (colored red in the figure). The number of subsets is $2^{m-1}$. Thus we have m choices for $k$ (since $k \neq m$) which gives $m$ maximal chains , and $2^{m-1}$ chains that are a subset of each of these maximal chains, we have $m\cdot 2^{m-1}$ choices.

For $k=m$, we have to find the subsets of chains on the top row. Since there are $m$ terms from 2 to $2^m$, we have $2^m$ chains in this case.

So totally we have $m\cdot 2^{m-1} + 2^m = (m+2)2^{m-1}$ chains.

I liked solving the problems and it was balanced for an RMO. I am suspecting the cut-off is upwards of 50 points since 3 problems were doable by standard problem solving techniques. I think it will be less that 70 since I think very few students will get upwards of 4 problems. I will update this post once the actual cutoff is released.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: